As the border guard took a look at my passport, it dawned on me that I was about to complete one of the craziest journeys of my life. There was a mixture of emotions as I stood surrounded by Russian soldiers with AK47’s. How did I get here? Lets rewind a little!

In this post, I want to take you on a journey to one of the least visited regions in the world. The region, which is locally known as Pridnestrovie (or Transnistria internationally), is a breakaway region which lies between Moldova and Ukraine. It’s name literally translates to “the area next to the Dniester river”, which flows through the region.

The journey begins in a bus station in Chisinau, the capital of Moldova (Europe’s least visited UN recognised country). The story of my Moldova trip is another crazy adventure, which I will talk about another time!

When I say that the story begins at the bus station, you probably have a certain image in your head. Let me try to set the scene a little bit more accurately.

In many former USSR countries, there are generally two types of busses that you’ll encounter. First are the large busses such as the one in the image above. These are similar to the ones you find in any western countries with the caveat that its still quite common to find trolley busses here as well. These busses usually run in loops around the city and follow a regular schedule. Many are electric and draw power from overhead wires, which adds to the old-school charm of many cities.

Then there’s the marshrutka, which is a staple of post-Soviet public transport. Marshrutkas are minibus-style vans that serve as flexible intercity and regional transport. They typically operate on fixed routes, but without the structure of a formal timetable. The big idea is that while trolleybuses handle the busy urban routes, marshrutkas step in to serve smaller towns, villages or places less travelled.

The story begins at a marshrutka hub in the middle of Chisinau, which resembles a chaotic open-air car park scattered with minibuses. Around the edges, kiosks line the perimeter, where you can buy tickets (if you know what to ask for) or stores selling snacks. Sandwiched anywhere they can find, locals sell homegrown produce, using the hustle and bustle as a chance to earn a few extra lei.

The first challenge? Finding your bus. If it exists!

You see, the marshrutka system is based more on demand than strict scheduling. Buses are added to routes depending on expected passenger numbers and they don’t leave until they’re full. That means timing is fluid and planning is… optimistic. Especially when you are heading to one of the least visited places in the world.

Today I was lucky. As I was wandering through the chaos, I caught a sight of a man holding a sign that read “Тирасполь” (Tiraspol written in Cyrillic). Despite being a whole country away from Russia, Russian is the most commonly spoken language in Transnistria. This is due to a rich and complex history (which I will go into later).

I approached the driver, who gave me a quick nod and pointed toward a nearby kiosk where I could buy a ticket. Moldova isn’t exactly a hotspot for international tourists, so English is rarely spoken. I had to rely on my Russian to buy the ticket. The woman in the kiosk didn’t seem fluent in Russian either and was likely a native Romanian speaker. After a few polite misunderstandings and some awkward gesturing, I purchased a ticket, which cost the equivalent of £1 for the two-hour journey to Tiraspol.

Back at the marshrutka, the driver gave a short call and began waving everyone on board. The marshrutka itself was… snug. While the seats were actually more padded and comfortable than the rigid worn ones on larger busses, the space was tight. I found myself wedged shoulder-to-shoulder between a group of Moldovan passengers who greeted me with warm smiles, nods and curious glances.

The windows were slightly cloudy due to the dusty roads and the faint scent of diesel filled the air. As we began to pull out of the station, the driver turned on a small radio and played some tinny Moldovan pop songs. The other passengers were probably preparing themselves for a long wait at the border due to me being a westerner.

The journey to the boarder was far less dramatic than I had previously anticipated. Most of the other passengers sat in silence and the roads were smoother than the ones I had experienced on the way to Chisinau a few days prior. Out of the window, I could mostly see farmland and houses in various stages of construction. One thing that stood out were the half-built homes, which is a common sight in many posts-Soviet countries.

In Moldova, where salaries are low and access to credit is limited, homes are often built gradually over many years, sometimes even decades. It’s not unusual for multiple generations of a family to contribute to the construction. Typically, they will complete the ground floor first and move in while work continues around them. The upper floors and exterior facades are left as bare brick and concrete until time and money allows the next phase. As a result, it’s completely normal to pass rows of houses with rough concrete shells, unfinished balconies and metal rebar protruding from the rooftops.

After a few brief stops to drop off and pick up passengers along the way, the minibus eventually came to a complete halt. But this time felt different.

We had arrived at the border.

It wasn’t at all what I was expecting. There were no official-looking booths, no barriers and no imposing infrastructure. Instead, a wooden table sat at the side of the road underneath a parasol style umbrella. Two guards were sat at the table casually smoking and chatting amongst themselves. One by one, we stepped off the bus. The guards took a quick look at our passports, gave a nod and motioned for us to get back on board.

I was a bit confused about the whole situation. Everything I had read beforehand had warned that the Moldova-Transnistria border was strict and intimidating. As the bus began to move forwards, I felt the tension in my shoulders begin to ease. I thought that maybe the stories had been exaggerated.

That was until we stopped again a few hundred yards down the road.

I quickly realised that I had only passed through the Moldovan side of the border. The real crossing still lay ahead.

You see, since no UN recognised country actually recognises Transnistria as an independent state, it is still seen as a part of Moldova. So that first checkpoint? Merely a formality. I’d understand this more clearly later in the day, when I exited Transnistria from the opposite side.

But now, lying ahead, was the Transnistrian border I had read about.

The checkpoint was painted in bold red and green, the colours of the national flag, with a large hammer and sickle displayed at its centre. A striking reminder that the Soviet Union might have collapsed elsewhere, but here it still existed.

I could feel the tension rise as Russian-speaking soldiers approached the minibus, barking orders at us to get off. They wore stern expressions and carried AK47’s slung over their shoulders. It was at that moment that the reality of where I was truly began to sink in.

I felt a sudden chill of anxiety as I slowly rose from my seat and stepped out onto the cold tarmac.

The border guards clearly recognised the locals, giving them a quick glance and waving them through with little more than a nod. When one of them turned to me, however, he paused. He looked me up and down for a moment, then snapped “русский?”

Due to ambiguity in the Russian language, I couldn’t tell whether he was asking whether I am Russian or whether I spoke Russian. My heart pounding, I replied back in Russian “Yes, I speak Russian but I am British”.

With a disapproving look, he pointed me towards a nearby building with a small window and the Cyrillic letters “ПМР” displayed above it.

I recognised the initials: Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, which is Transnistria’s official name.

As I approached the small window, I was suddenly aware of several Russian soldiers closing in around me, their rifles no longer slung over shoulders but held firmly in their hands. Across the road, in a shallow ditch, I caught sight of a Russian tank, its turret manned by soldiers gripping mounted machine guns.

One wrong move, I thought, and I could be in a world of trouble.

Behind the glass, a woman with a cold, sharp voice asked for my passport in Russian. She began questioning me, asking where I was going, why I was visiting and how long I planned to stay. Her tone was sharp and the whole thing felt more like an interrogation than a formality.

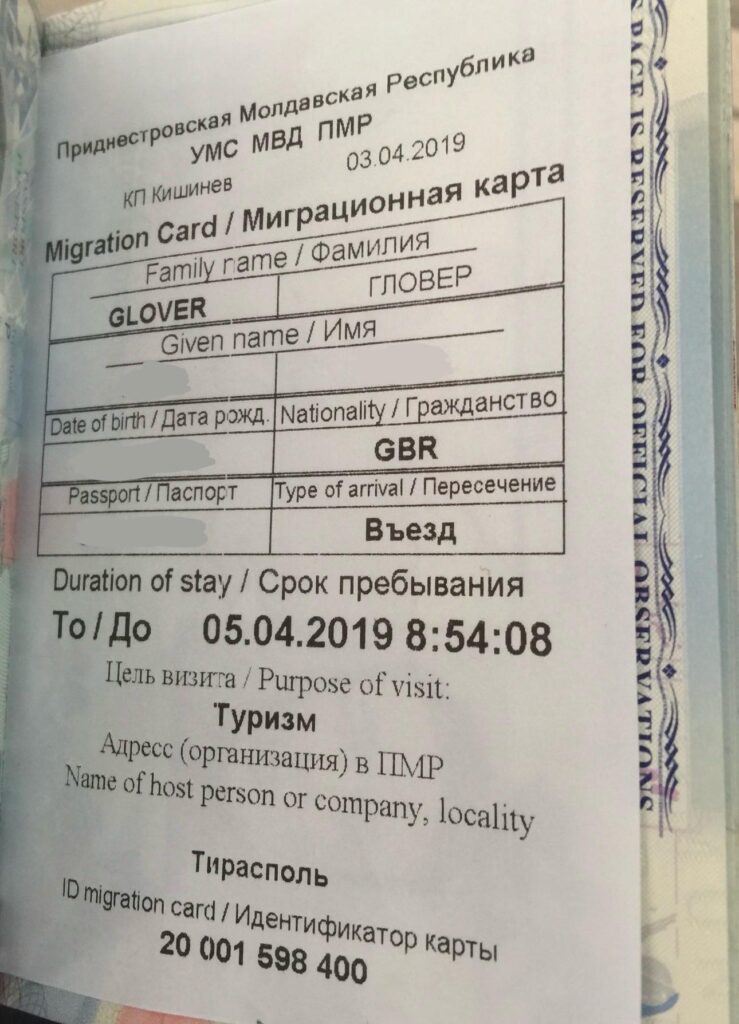

At one point, she hinted rather clearly that a “gift” might help speed things up or make things easier. I had read before that border officials sometimes expect small “tokens of appreciation”. I gave a slight nod and eventually she handed me a small slip of paper.

“Don’t lose this”, she said. “It’s your way out”.

She gestured for me to return to the bus. I walked back carefully, avoiding eye contact with the guards, who were still watching me closely.

As I climbed aboard and shut the door behind me, I could feel the irritation in the air. The other passengers had clearly been waiting a while and their expressions weren’t exactly welcoming.

To be honest, I didn’t really care. I just wanted to get away from the border.

As the minibus pulled away from the checkpoint, I stowed the flimsy paper visa like it was the most valuable thing I owned. Outside the window, the unfamiliar landscape of Transnistria began to unfold. What lay ahead, I didn’t quite know.

In the next episode of this blog, I will share what happened once I arrived into Transnistria.